By: Jon Finkel

You meet a guy in his late 40s whose last name is DiMaggio or Killebrew or Aaron and yes, you naturally wonder if his dad isn’t Joe or Harmon or Hank. But you meet a guy with a seemingly ordinary last name and you think nothing of it. In fact, when said guy tells you that his dad once hit .302 with 46 home runs and 141 RBIs in a single major league season, you can’t help but be skeptical. A player puts up those kinds of numbers, even once, you should know who he is if you’re a baseball fan.

If it happened during the mid-1990s or early 2000s, when mediocre players were hitting meteoric home runs, maybe, just maybe, a guy accumulates those numbers and his name isn’t the first or second to pop into your head. Maybe it gets lost in the crazed era of crazy stats. Maybe.

But if a guy puts up those numbers in the 1960s, you figure after enough guesses, you’ll land on the right name. It has to be Willie Mays or Frank Robinson or somebody. Hell, Carl Yastrzemski won the Triple Crown in 1967 with less gaudy numbers (.326 / 44 / 121), so this guy’s gotta be on the tip of your tongue. But he’s not. That season doesn’t belong to Ernie Banks or Brooks Robinson or Roberto Clemente or any Hall of Famer you can think of. It belongs to Jim Gentile.

“Who?” You’re probably thinking.

Exactly.

***

Looking back on the 20th century of baseball, there are only a handful of years where you would absolutely, positively not want to have the best season of your career if you have any hopes of it being remembered.

1919 would be a good year to avoid, as stealing headlines away from the Chicago Black Sox scandal might be impossible. It’s not every day a team throws a World Series.

1941 would be an equally wise year to stay away from. When Ted Williams bats .406 and Joe DiMaggio hits in 56 straight games, well, unless you hit .407 or put together a 57-game hitting streak, you’re doomed to be forgotten.

Then there’s 1961, perhaps the most iconic year in baseball history, when two of the best players on the most recognized sports team in the country chased down the most sought after record held by the most popular man ever to play the game. Surely, this would be the No. 1 season to steer clear of.

How can you compete with Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris while they’re in a dog fight for Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record in Yankee Stadium for an entire summer?

In short, you can’t.

***

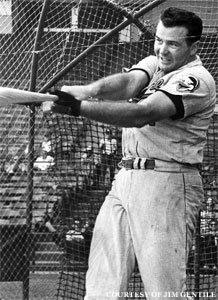

The Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jim Gentile to a contract right out of high school in 1952. He stood 6-3, weighed more 210 pounds and he had such a ferocious swing that team management asked him to wear a sponge on his hip so he wouldn’t bruise his bone when the bat whipped around his body.

“I tried it, but one time I swung so hard the bat bounced off the sponge and slammed into a catcher’s head,” Gentile says. “I stopped using it after that.”

He had a cannon for an arm, too.

“I signed out of high school as a pitcher and a first baseman,” he explains. “I got out of school in June. On the first of August, they called and said they wanted me to play in Santa Barbara because a pitcher got hurt and they needed somebody to take his spot. The first game I pitched I had a no-hitter into the seventh inning, but I finished the season with two wins and six losses with an earned run average of around three. The next year, when I showed up at my team in Fort Worth, they asked if I wanted to play first base or pitch. I chose first.”

And thus, the big lefty embarked on a successful, yet at times, wildly frustrating career as a power hitter in professional baseball.

“My first year in single ‘A’ I hit 34 home runs and led the league,” he says. “The next year, in double ‘A’, I led that league in home runs. But none of it mattered because the pecking order was in stone. Norm Larker was ahead of me in triple ‘A’ and Gil Hodges was ahead of him on the Dodgers. There was nowhere for me to go.”

To the current crop of baseball players and fans, Gentile’s plight must seem surreal. His agent couldn’t do anything? There were no agents. What did the players union think about it? No union either. Couldn’t he just wait a year or two until free agency? No such thing as free agency.

These days, the very concept of feeling sorry for a baseball player is laughable. It’s almost impossible to feel sorry for them. It’s like trying to evoke sympathy for the royal family. In terms of their careers, how do you feel sorry for people who make millions playing a game for a living?

But that’s now. In the 1950s, minor league baseball players had about as much leverage over their team’s owners as a current Walmart cashier has over the Walton family.

“I’d ask Buzzie Bavasi, the general manager of the Dodgers at the time, ‘Why don’t you trade me?’ He’d say, ‘Nobody wants you’,” Gentile says, laughing. “I didn’t have an agent. We just didn’t know back then.”

Gentile says the team’s logic at the time was that, yes, maybe he could be a great first baseman. But the Dodgers already had a great first baseman; and it’s better to have two great first basemen, even if one’s stuck in the minors, than for your opponent to have one. It was that mindset that kept him from being traded. In the meantime, he continued to dominate the minors.

“In 1956, I hit 40 home runs in double ‘A’ ball in Fort Worth,” he says. “I got invited to tour in Japan with the rest of the Dodgers team after the season ended and I caught fire. While we were overseas, I led the team in home runs, runs batted in, batting average, almost everything. That’s when Roy Campanella gave me my nickname, Diamond, because he said I was a diamond in the rough.”

One particular memory during that trip led Gentile to believe that he might never get to play in the big leagues for the Dodgers. It happened when he came up to bat with the bases loaded and the Dodgers’ manager, Walter Alston, told Jim Gilliam, who was on third, to steal home.

“That’s when I knew Alston didn’t care for me,” he says. “Gilliam tried to steal home and he got called out.”

So what happened next?

“I hit a three-run homer,” he says, laughing.

During that trip Gentile also became good buddies with Campanella.

“Roy was one of my friends,” Gentile said. “We’d go out to dinner in Japan and I’d say, ‘Campy, I don’t know what to do. I understand Gil is the best first baseman in the National League, but I want to play’. He just said, ‘When the time comes, you have to take advantage of it’. Nowadays, a guy can go straight from Double-A to the majors. Back then, you had to wait your turn, no matter how long it took. I didn’t get mad at anybody as this went on. In the meantime, I kept playing ball.”

That last phrase is an understatement, as Gentile would bounce around the Dodgers minor league system, often playing three games in a single day.

“I’d play in the morning in Single-A, then in the afternoon in Double-A, and then I’d play in the night game for the Triple-A club,” he says.

And then, finally, he got his shot.

***

“I was playing in Panama when Joe Altobelli walked up to me and told me, ‘Congratulations, you’ve been traded to Baltimore,'” Gentile says. “Then he said, ‘It’s too bad, that’s a big ballpark, you’re gonna have to hit it twice to get it out of there’.”

The Orioles paid $50,000 and two players for Gentile, but he was only sent to Baltimore on a trial basis for 30 days.

“If they didn’t like me after thirty days, they could send me back and get back half the money,” Gentile says.

Yes, you read that right. A professional baseball player was traded with a return policy.

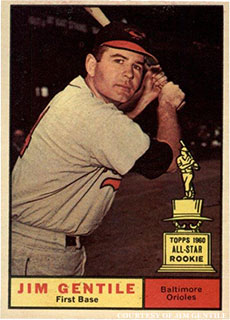

Fortunately, the Orioles didn’t have to worry about finding the receipt for Gentile’s purchase to bring him back because they decided to keep him. (The fact that he was an All-Star, almost won Rookie of the Year, and finished 15th in MVP voting made that decision quite easy.)

That was in 1960, one season before Gentile would harness all of his talent to post one of the most impressive seasons by a first baseman in his generation.

***

“By 1961, I had been in the game long enough to know what I was capable of,” Gentile says. “I had a big swing and I knew I could hit anywhere between .250 and .270 and hit about 25 home runs. At the time, if you hit 25 home runs you were pretty good. I just knew my ability.”

The season started just like any other, with Gentile going along, trying to help his ball club win games. He didn’t have the long guaranteed contracts that players have today, so he took each game seriously, for fear of not being signed the following year. Then on May 9, just a month into the season, he had a game that would be a sign of things to come.

During a 13-5 victory over the Minnesota Twins, Gentile hit two grand slams on the way to a nine-RBI game (he drove in one run on a sacrifice fly). He would go on to hit three more grand slams that year and, just like in that game, almost everything broke his way. If not for the nightly fireworks taking place about 200 miles to the north at Yankee Stadium, Gentile would have been the talk of the league.

“Right around the All-Star Game, the three of us, me, Mickey and Maris, were all at about 25 or 26 home runs,” Gentile says. “Mickey hit from both sides of the plate and he was one of the greatest players in the game. I would have loved to be able to copy Maris’ swing. He just had a beautiful swing.”

Gentile admits that he didn’t talk to Mantle or Maris much at the All-Star Game that year, though he did get a picture with them and a few other All-Stars.

“To tell you the truth, I always felt like an outsider,” Gentile says. “I never felt like I was in their league.”

After the All-Star Game, when the pennant races started to heat up, so did the daily back and forth in the home run race between Mantle and Maris.

“We had about the same home runs mid-summer,” Gentile says. “Then, all of a sudden, they were closing in on 40 and I was only closing in on 30.”

Lost in all of the attention was the fact that Gentile had a higher batting average and more RBIs than Mantle and he went RBI for RBI with Maris the whole year.*

Still, nothing could compete with the buzz created by two Yankees chasing the immortal Babe Ruth and his home run record.

When the dust settled, and Maris finished with 61 home runs to Mickey’s 54, they were locks to finish one-two in MVP voting, leaving Gentile as the owner of one of the best seasons ever to not win the award. Gentile even finished with a higher slugging percentage and on-base percentage than Maris, who came out on top. Such is the price you pay when you do battle with the giants of the game.

Sixty years later, when Gentile is asked if he’d change anything about that season, he laughs and says, “I would have liked to have done it in ’62!”

It helps to have a sense of humor about these things.

***

After his season-for-the-ages, Gentile got a small taste of the life of a major league baseball star when he went on a home run derby tour of the south with Harmon Killebrew and Roger Maris.

“We’d go to four different towns, sign autographs and then hit 20 balls,” he says. “It was a way to meet the fans and make some money.”

He says he never discussed either his or Maris’ historic season while they were on tour together and even laughs at the idea.

“When ballplayers used to get together, we didn’t really discuss baseball,” he says. “I wasn’t going to sit down next to Roger Maris and say, ‘Hey, how’d you hit 61′!”

Of course, as a sign of the times, when the home run derby tour was over, Gentile didn’t head to a cutting-edge facility to resume an off-season workout because there was no such thing.

“When I played they didn’t want you lifting weights, so most of the time to stay in shape you did your own exercises or you ran,” he said. “When I was in high school, I used just a hand squeezer every night until it felt like my arms were going to blow up. I also used to swing a heavy lead bat, but that’s all we’d do.”

No, unlike today’s players who finish the season and film commercials and eat food prepared by a personal chef and exercise with top-flight trainers, Gentile finished one of the greatest seasons of his life and went back to an off-season job at a car dealership.

“I wasn’t much of a salesman,” he says. “I was more like a maitre d’, welcoming people and being paid to be there for baseball fans.”

Gentile knows that if he had his 1961 season in 2021, he wouldn’t be working at a car dealership, rather, he’d own one. Or ten.

“I would love to play now,” he says. “The big thing nowadays is that players stay in shape all year round and they don’t have to go to work. I think the players are fantastic, though. Every decade they get stronger and some of the plays they make in the outfield are spectacular. I still watch the Orioles when I can. They have an exciting young team.”

Does he have a favorite modern player? Derek Jeter, perhaps? Or a first baseman like Albert Pujols?

“I like Nick Swisher,” he says. “He plays hard.”

An under-the-radar answer from the man with the one of the most under-the-radar great seasons in baseball history.

If you didn’t know his name before, now you do:

Jim Gentile: .302 / 46 / 141 – 3rd Place AL MVP – 1961

Did you love this article? Sign up for my Books & Biceps weekly e-mail here.

* In 2010, it was discovered that Roger Maris was accidentally given an extra RBI in a game against the Indians on July 5th, 1961. Maris finished 1961 with one more RBI than Gentile. When statisticians removed the extra RBI, Gentile officially tied Maris for the league lead, with 141.

*This article originally ran on www.ThePostGame.com